Community… what a heartwarming idea and one that is used so often. So often, in fact, the vital essence of the word is often lost. Is a forty-apartment high-rise building always a community of people? Is a newly-built subdivision containing sixty modern homes necessarily a community? Both venues may develop into a group with a common cause, purpose or belief that may be worthy of the label community, or perhaps they may simply be a neighborhood, a people or some other title without a binding factor. Merriam-Webster defines community as “a unified body of individuals; a group of people with a common characteristic or interest living together within a larger society.” The Cambridge English Dictionary states similar words enlarging on the idea as “a unit because of their common interest, social group, or nationality.” Regardless of its common use in today’s world, the word community stirs one’s heart and brings a sense of order and respect to our thinking.

The early settlers in the southern regions of the new state of Kentucky certainly felt the importance of community. They settled on the land on which they had a claim, built their shelter, planted crops and hunted wildlife, fought off whatever disasters may have occurred, knowing all the time a community of other homesteaders were nearby and shared their efforts – binding them to each other. Often it was the local worship gatherings that sealed their relations. Usually, it was a convenient setting of some area member who ran the mill or supply store or maybe the repair shop.

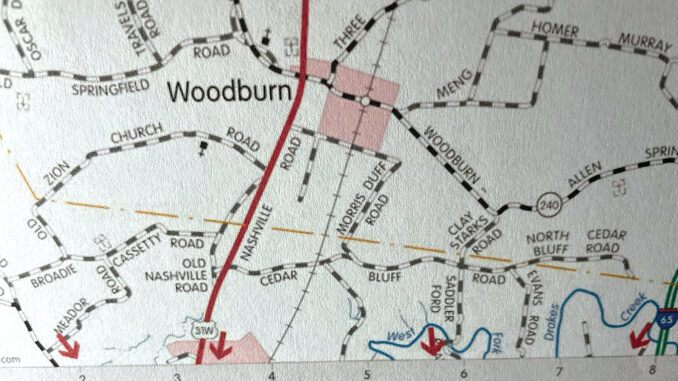

Mason’s Inn was such a place. Located about eight miles southeast of Bowling Green, it was the center of the area. It was established on the Cumberland Trace Trail, running from the Kentucky settlement to the Tennessee settlement, and became a stagecoach stop. It remained the hub of the settlements in the area until the Louisville and Nashville Railway in 1859 made a depot stop at its rail line. This rail stop brought passengers and delivered needed supplies to the local farming area, as well as merchandise for the town’s growing needs. The depot would handle livestock, cattle and pigs, tobacco, produce and other locally-raised products for sale in other markets. It was practical for the settlers to move their operations to the rail site. No longer a hamlet called Mason’s Inn, New Woodburn, or simply Woodburn, gradually became an evolving townsite.

One hundred sixty years ago the name New Woodburn, and later simply Woodburn, was believed to refer to a local woods nearby that had been destroyed by a fire. It was also a familiar name back in the thirteen colonies from which many of early settlers had remembered.

Meanwhile, the newly-founded town was developing steadily. It was formally incorporated on February 5, 1866. Before its official recognition, loading docks were built along the railway. Homes were built facing the train lines. Merchants built shops and newcomers were drawn to area, making the town fan out away from the train tracks on each side. Joining the blacksmiths, plow makers and saddle-making skillsmen were shoemakers, dressmakers, doctors, hotel managers, a post office and a host of other talents that made Woodburn a desirable community with a population around one thousand near 1876. One amazing fact during its expansion from a hamlet to a bustling township – the people never lost their sense of community. The residents experienced a setback during the Civil War when the Confederate rebels burned down the depot in the soldiers’ attempt to interfere with the railway’s effectiveness. The structure was rebuilt, only to have it burned again some years later. By then, the markets in Bowling Green had increased so much the Woodburn depot stop was discontinued. Local business began to slowly close as the traffic between Woodburn and Bowling Green increased. The nearby farms began relying more on the bigger city for markets and supplies. Population in the township lowered from one thousand in the 1870s to the two-then-three hundreds, resting in 2020 to three hundred three.

The age of the bustling community can still be viewed by visitors today. Though many of the buildings are abandoned and stand empty, the majesty of the past years can be felt. The most delightful view is a walk past the magnificent homes with their characteristics still worthy to see. To walk down Main Street, to wander past the homes with a welcoming wrap-around porch, to stand in front of the William Robb House on Clark Street – is to feel once again the beauty of life in this place one hundred sixty years ago. This was and is a vibrant community in the true meaning of the word.

Flash forward to the 1900s, 1937 to be exact, and this togetherness can be viewed vividly. Woodburn was awash with rain like the rest of Kentucky. It was not on a river like Bowling Green, but the raging tributaries were enough to flood the area. Added to this flow was the rising Skiles Lake. This body of water was a subterranean-fed body of water which overflowed into the community. For four to six weeks, Woodburn had no roads in or out of the city. Boats had to be used to serve the people and meet their needs. Schools were closed for nine weeks. The school bus, a horse-drawn wagon serving the area school settings, could not make its runs. However, Joe Meng, a thirteen-year-old riding on his favorite pony, never missed a day delivering mail to the affected members of the postal route. Community spirit existed at its best level and proved once again the character of the people of this Warren County township.

For a most delightful reporting of the early days of the Woodburn story, the reader would enjoy reading, “History of Woodburn”, written by a native resident, Mrs. H. M. Blackburn, a copy of which can be found in the Kentucky Museum Library. It is thrilling to read of individuals living at the time of Mason’s Inn, of their efforts to move from “Old Woodburn” to Woodburn when the train stop occurred, of how the passengers riding the first train to celebrate its arrival in Nashville had to ride on wooden chairs on an open flat car. Published by editor John B. Gaines, who was born in “Old Woodburn” and grew up in the new town, this historical writing is an enjoyable account of the community.

Community is truly a remarkable vocabulary word. Perhaps it is overused, but we appreciate the binding factors that unite individuals. United by religion, by political group, by work or school setting, or by a vast number of interests, most people enjoy existing in communities.

-by Mary Alice Oliver

About the Author: Mary Alice Oliver is a Bowling Green native who is a 1950 graduate of Bowling Green High School. She retired from Warren County Schools after 40 years in education. Visiting familiar sites, researching historical records and sharing memories with friends are her passions.