Maya Angelou said, “The more you know of your history, the more liberated you are.” Knowing where and how our ancestors lived helps us understand them better and ourselves better. All genealogy can be challenging but finding African American ancestry is a special challenge. Sometimes getting started is a struggle.

All genealogy searches start with interviewing the living family, community elders, and all who might remember names and places related to your particular search. Use old photographs to spark memories. Take copious notes during the interviews. Places and dates, even if vague, are nuggets of information that help pinpoint details later on.

Once you have your family stories recorded, try using online resources. Two major sites are Familysearch.org (free to use) and Ancestry.com (free for library card patrons.) Look for records detailing the census, births, deaths, marriages, military careers and immigration journeys. Start with the most recent census and work your way back. Look for marriage records to help find women’s maiden names. Include siblings, because they help recognize other family groupings when names change. Death certificates and cemetery records will often list parents’ names, as well as birthplaces.

However, many of these records are hard to find for African Americans prior to emancipation. Their names are missing from registers of births, deaths or baptisms. On pre-emancipation censuses they are tally marks, their age and sex the only evidence of their individuality. Finding their history is tricky, but some information can be unearthed by digging through all records of a geographical location, including federal, state, county and local resources.

A common avenue of inquiry for finding names of the enslaved people is finding the names of their owners. With that information you can look into probate records, which often lists the enslaved persons inherited by the dead owner’s heirs.

For example, Delphia Sears, who died in 1896.

An online search tells us that in the 1880 U.S. census she is 68 and lives in Bowling Green, KY. She is buried in Mount Moriah Cemetery, as listed on Find-a-Grave.com, and from her will, found on Ancestry.com, we discovered she owned property in Bowling Green, which gives us her children’s names. We know from her age she was very likely an enslaved person. Sometimes enslaved persons took the name of their former owner, so looking for Sears in the Warren County Kentucky Inventory of Estates with Wills 1823-1827 by Sandra K. Gorin, we find Phillip Sears and his wife Jane, formerly the widow of a man named Jason Isbell. The estate of Jason Isbell included a girl named Delphia, aged about 13, with her mother Nanney, aged about 36 or 37, along with her siblings, Green, Richard and Constantine. Delphia and Richard were entailed to the widow, who by that time had remarried Phillip Sears. Two years later Delphia is listed in another will, that of James S. Isbell, along with her mother and siblings, as well as a new 9-month-old sister, Antsajane. So we know Delphia’s mother’s name is Nancy, and she has at least four siblings. We might find more by looking for Isbell or Sears family letters and other probate documents.

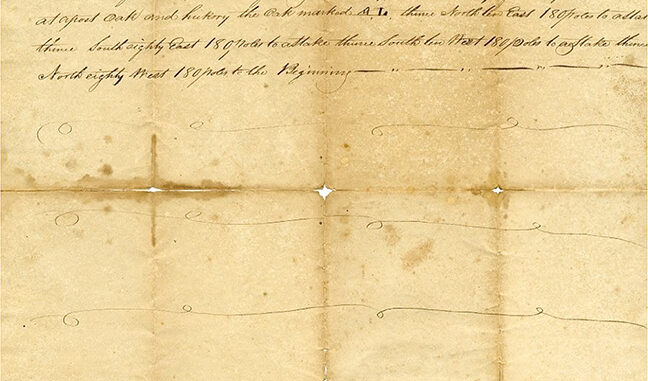

An additional resource for our area is Deed Abstracts of Warren County Kentucky by Joyce Martin Murray. There are two volumes, 1797-1812 and 1812-1821. These are compiled abstracts for deed books, which record mostly land transactions and include transferral of other types of property, such as enslaved people, as well as apprenticeships, attorneys in fact/trustee appointments and emancipations. In one entry, dated 7 April, 1807 Samuel Caldwell sold to Robert Moore “a negro girl Lidia,” for $200. Moore, one of the founders of Bowling Green, then deeded Lidia to his daughter Sally Grider with “love and affection.”

In the 1800 U.S. census for Warren County, Kentucky, there were 431 enslaved people and four free people of color. The earliest known African American landowner in Warren County was Abraham LeVaugh. His land grant states that he had 200 acres “in a grove on the north side of the Big Barren River” and is dated July 6, 1799. LeVaugh was here prior to that, however, and appears in the 1795 Census of Kentucky as Abraham “Levaw.” According to the Early Tax Lists of Warren County, Ky. 1797-1807 compiled by Barbara Ford and Patricia Reid, he paid taxes in 1797, 1799, 1800, 1802-1806. Additionally, in the Deed Abstracts of Warren County Kentucky 1812-1821, in 1815 he bought 75 acres more, for $75, and then a few months later sold 123 acres for $80. Censuses prior to 1850 do not list any other household members by name, but by age range. However, we know from local court and bank records found in the archives at Western Kentucky University, that his widow, Elizabeth, and children, Abraham, Jr., Ezekiel, Isaac, John, William, Maria and Polly were sued March 16th, 1830 for the remainder of a mortgage on his property, a total of $77.

If you need help with your search, submit a request at https://warrenpl.org/genealogy/request/. This free service is not limited to genealogy questions; we also take general history inquiries. If you’ve ever been interested in finding out more about your relatives but don’t know how or where to start, reach out today.

-by Amy Wilk